Charting a Course to Blue Ocean Strategy

Guy Laliberté: From Street Performer to Head of Cirque du Soleil

Guy Laliberté, a former accordionist, acrobat, and fire-eater, is now the head of Cirque du Soleil, one of Canada's largest cultural export companies. Founded in 1984 by a group of street performers, the company has already introduced its productions to nearly forty million people in ninety cities around the world. In less than twenty years of its existence, Cirque du Soleil began to receive the kind of profits that Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey - the world champions of the circus industry - managed to achieve only after more than a hundred years after their appearance. This rapid growth is also remarkable in that it occurred not in an attractive, but in a fading industry, where a traditional strategic analysis indicated limited growth opportunities.

Creating a New Market Segment

Another interesting aspect of Cirque du Soleil's success was that the company did not win by poaching customers from the declining circus industry, which was historically focused on children. Cirque du Soleil did not compete with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. Instead, the company created a new, untapped market segment, free of competitors. It targeted an entirely new group of consumers: adults and corporate clients willing to pay several times more than a regular circus ticket to see a new, unprecedented show. The name of one of Cirque du Soleil's first projects spoke for itself: "We are reinventing the circus from scratch."

Blue Oceans vs. Red Oceans

Cirque du Soleil succeeded because it understood that in order to win in the future, companies should stop competing with each other. The only way to beat the competition is to stop trying to beat it. To understand what Cirque du Soleil achieved, imagine a market universe consisting of two oceans: red and blue. The red oceans symbolize all existing industries at the moment. This is the known part of the market. Blue oceans denote all industries that do not yet exist today. These are unknown areas of the market.

In red oceans, industry boundaries are defined and agreed upon, and the rules of the competition game are known to all. Here, companies seek to outperform their rivals in order to attract a greater share of existing demand. As the market becomes more and more crowded, the chances for growth and profit making keep falling. Products become commodities, and ruthless competitors cut each other’s throats, turning the red ocean blood red.

In contrast, blue oceans denote untouched market areas which demand creative approaches and offer opportunities for growth and high profits. Although some blue oceans emerge beyond the established industry boundaries, most blue oceans emerge within red oceans by expanding the existing industry boundaries, as Cirque du Soleil did. In blue oceans, competition is irrelevant because the rules of the game have yet to be set.

Creating Blue Oceans

Cirque du Soleil succeeded because it understood that in order to win in the future, companies should stop competing with each other. The only way to beat the competition is to stop trying to beat it. This book offers you practical patterns and analytical tools for systematically finding and capturing blue oceans. Unfortunately, blue ocean maps are almost non-existent. All major developments in strategic thinking over the past twenty-five years have focused mainly on competition-based red ocean strategies. As a result, we know a lot about battling competitors in red waters, from analyzing the underlying economic structure of an industry and choosing strategic positions - low cost, differentiation, or focus - to benchmarking competitors. Debates on blue oceans continue without interruption. However, there is very little practical guidance on how to create such oceans.

The Evolution of Industries

Blue oceans have always been created. Although the term blue oceans is quite new, the same cannot be said about the oceans themselves. They are an integral part of the business world of the past and present. Look at the world a hundred years ago and ask yourself: how many of today's industries were completely unknown back then? The answer is that such fundamental industries as automotive, sound recording, aviation, oil refining, healthcare, and management consulting were either unheard of or just beginning to emerge at best.

Fast forward just thirty years. Again, you can list dozens of multibillion-dollar industries such as mutual funds, mobile phones, gas power plants, biotechnology, retail discounters, express couriers, minivans, snowboards, coffee bars, and home video recorders - and that's far from all of them. Just three decades ago, not one of these industries really existed. Now let’s move the clock forward twenty or fifty years and ask ourselves: How many still unknown industries will there be then? If history is any predictor of the future, the answer is many.

The truth is industries have never been static. They continuously evolve. Their performance improves, markets expand, and players come and go. History makes it clear that we have seriously underestimated the possibility of creating new industries and re-creating existing ones. However, strategic thinking still focuses mainly on red ocean strategies related to competition.

Quantifying the Impact of Blue Oceans on Profit and Revenue

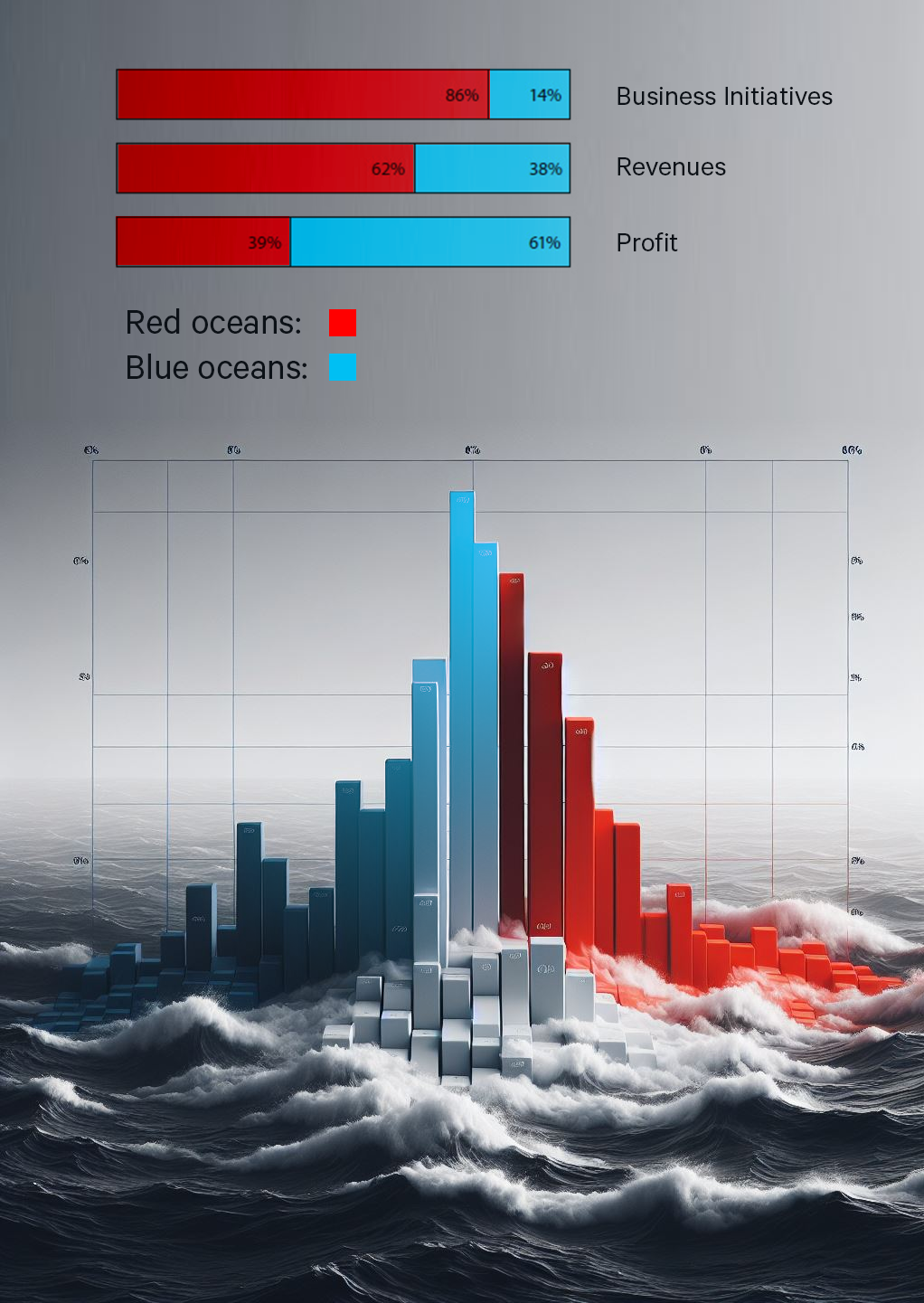

In the course of studying the business initiatives of 108 organizations, we tried to quantify the impact of blue oceans on profit and revenue (Fig. 1.1). It turned out that 86% of initiatives represented a linear expansion, that is, they involved gradual improvements in the existing market space - within the red oceans. They accounted for only 62% of total revenue and 39% of total profit.

The remaining 14% of initiatives were aimed at creating blue oceans. They generated 38 and 61%, respectively. Given that business initiatives included all investments in creating red and blue oceans (regardless of the size of the revenues and profits they generate, including completely failed projects), the benefits of creating a blue ocean are obvious. And although we do not have data on the success rate of initiatives in red and blue oceans, the above overall differences in their effectiveness speak for themselves.

Fig. 1.1. The impact of creating a blue ocean on growth and profit

The Growing Need to Create Blue Oceans

Behind the growing need to create blue oceans lies a number of driving forces. Technological advances have greatly increased production efficiency and allowed suppliers to produce unprecedented volumes of products and services. As a result, supply exceeds demand in many industries. Globalization exacerbates the situation. As national and regional borders fade and information about products and prices spreads instantly around the world, niche markets and monopolistic domains continue to disappear. Supply is increasing due to global competition, but there is no evidence of increasing demand worldwide, and statistics even point to declining numbers of participants in many developed markets. The result has been an ever-increasing commoditization of goods and services, more severe price wars, and declining profits.

Recent research on major American brands within an industry confirmed this trend. According to the research, brands in major product and service categories are becoming more and more similar, and as they become more similar, people are increasingly making their choice based on price. Unlike the past, the consumer is no longer willing to wash only with "Tide." And he will not cling to "Colgate" if "Crest" toothpaste is on sale at discounted prices, and vice versa. In areas crowded with manufacturers, it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between brands in both economic upturns and downturns. All this means that the business environment that gave rise to most strategic and managerial approaches in the 20th century is gradually disappearing. More and more blood is being spilled in the red oceans, and managers need to pay more attention to the blue oceans than the hordes of current managers are used to.

From Company and Industry to Strategic Move

How can a company break out of the red ocean of fierce competition? How can it create a blue ocean? Is there a systematic approach that can ensure that a company achieves this goal and thus maintains high performance? When we started looking for answers, our first step was to define the basic unit of analysis for our research. To understand where high performance comes from, the company is usually used as the main unit of analysis in business literature. People do not cease to admire how companies achieve significant growth and profitability rates, having an exquisite set of strategic, operational and organizational characteristics.

However, we asked a different question: are there any "exceptional" or "visionary" long-lived companies that constantly outplay the market and create blue oceans over and over again? Take, for example, the books "In Search of Excellence" and "Built to Last." The bestseller "In Search of Excellence" was published twenty years ago. However, two years after its publication, some of the companies studied by the author - Atari, Cheseborough-Pond's, Data General, Fluor, National Semiconductor - faded into oblivion. As stated in Managing on the Edge, two-thirds of the exemplary companies listed in the book lost their industry leadership position within five years of the book's publication. The book "Built to Last" continued the same theme. In it, the author sought to identify the "success habits of visionary companies" that had long experience of high performance. However, to avoid the mistakes made in "In Search of Excellence", the research period in "Built to Last" was expanded to the size of the company's life cycle, and only companies that had existed for at least forty years were analyzed. "Built to Last" also became a bestseller. However, upon close examination, some flaws emerged in the supposedly visionary companies examined in the book.

As shown in "Creative Destruction," much of the success that the author of "Built to Last" attributed to exemplary companies was more the result of the industry as a whole rather than the fruits of the companies themselves. For example, Hewlett-Packard (HP) met the criteria set out in "Built to Last" because it had long been ahead of the entire market. In practice, the entire computer components industry was ahead of the entire market along with HP. Moreover, HP did not even surpass all of its competitors within that industry. Noting this and other examples, the authors of "Creative Destruction" wondered if there were ever any truly "visionary" companies that had long been ahead of the entire market.

The Strategic Move: Key to Blue Oceans and High Performance

In addition, we all had the opportunity to observe the stagnation or decline of Japanese companies, which at the height of their heyday in the late 1970s and early 1980s were renowned as revolutionary strategists. If there are no eternally high-performing companies and if the same company goes from unprecedented success to decline, it turns out that the company cannot be considered a suitable unit of analysis in studying the sources of high performance and blue oceans.

As mentioned above, history also shows that industries have never ceased to emerge and expand and that industry conditions and boundaries are not constant; they are set by individual entities. Companies do not need to butt heads in the space of an industry; Cirque du Soleil created a new market space in the entertainment sector and, as a result, achieved powerful profit growth. It turns out that neither the company nor the industry can be considered the optimal unit of analysis for studying the sources of profitable growth.

In full accordance with this, our research showed that it is the "strategic move" - not the "company" or "industry" - that is the appropriate unit for explaining the creation of blue oceans and the permanent high performance of companies. A strategic move is a set of actions and decisions by management to develop a major business offer that opens up a new market. For example, in 2001 Compaq was acquired by Hewlett-Packard and lost its independence. As a result, many labeled the company as a failure. However, this did not devalue Compaq's blue ocean-focused strategic move to shape the server industry. These strategic moves not only became part of the company's powerful return to the market in the mid-1990s but also paved the way for a new multi-billion dollar market in computer hardware manufacturing.

Appendix A, "A Historical Overview of the Blue Ocean Creation Pattern," provides a condensed history of three quintessentially American industries, based on our database: the automotive industry - how we get to work; the computer industry - what we use at work; the film industry - where we go to entertain ourselves after work. As shown in Appendix A, there are no consistently successful companies or industries. However, the strategic moves that led to the creation of blue oceans and new trajectories of powerful profit growth are strikingly similar.

The strategic moves we are talking about - moves to create products and services that opened up and conquered new market spaces with sharply increased demand - are exciting stories of profitable growth, stories that make you think about the opportunities missed by those companies stuck in red oceans. We built our research around these strategic moves to understand how blue oceans are created and high business performance is achieved. We studied over one hundred and fifty strategic moves made between 1880 and 2000 in more than thirty industries and meticulously examined the business players involved in each of these events. The industries were extremely diverse: from hotels, film, retail, air travel, energy, computers, broadcasting and construction to automotive and steel.

We analyzed not only the winners who managed to create blue oceans, but also their less successful competitors. Both within each specific strategic move and across all strategic moves, we looked for similarities within the blue ocean creator group and among the less fortunate players stuck in the red ocean. We also looked for differences between these two groups. In the process, we tried to identify the common factors that led to the creation of blue oceans, as well as the key characteristics that distinguish the winners from the mere "survivors" and failures adrift in the red ocean.

As a result, after studying more than thirty industries, we found that neither industry characteristics nor organizational characteristics can explain the differences between these two groups. In assessing variable industry, organizational and strategy characteristics, we found that small and large companies succeeded in creating and capturing blue oceans, as did young and old managers, companies from attractive and unattractive industries, newcomers and dinosaurs, private and state-owned companies, representatives of low-tech and high-tech industries, as well as companies of very diverse national origins. Our analysis did not reveal a single permanently flawless company or industry. However, behind the seeming variety of success stories, we still managed to find a consistent and universal set of strategic moves to create and capture blue oceans.

Whether it was Ford in 1908 with its Model T; GM, which launched elegant emotionally appealing cars in 1924; CNN, which offered real-time twenty-four hour seven day a week news in 1980; or Compaq, Starbucks, Southwest Airlines or Cirque du Soleil, any other blue ocean cases we studied in our research, the approach to blue ocean strategy was always similar, regardless of industry.

Our research also covered famous strategic moves that led to radical changes in the public sector. And here too we discovered an amazingly similar pattern of action.

Revolutionizing the Circus Industry

Just as when the circus industry engaged in star wars, the so-called stars of the circus were pale in comparison to movie stars in the minds of viewers. And again, this tactic was very costly and had practically no impact on the audience. The idea of three rings also faded away. Such shows not only created tension for viewers forced to quickly shift their gaze from one ring to another, but also required a larger number of performers, leading to higher costs. Renting out premises for retail outlets and selling goods between rows seemed like a good way to make a profit, but in practice it turned out that the inflated prices kept viewers from making purchases and left them feeling cheated.

The Essence of Circus Appeal

All the perennial appeal of the circus boiled down to three main factors: the big top, clowns, and classic circus acts of various kinds of acrobatics and unicycling. Therefore, Cirque du Soleil retained clowns, but their humor became more subtle and refined rather than vulgar. The big top was refined, yet it was the big top that, ironically, many circuses had abandoned in favor of renting venues.

Revitalizing the Big Top Symbolism

Seeing that the big top alone was the symbol that embodied the magic of the circus, Cirque du Soleil created a classic circus symbol distinguished by its magnificent exterior finish and increased comfort. Such tents evoked thoughts of the great and legendary circuses. Sawdust and hard benches were removed. The acrobatic and other breathtaking acts remained but began to play a smaller role. They were made more elegant with an artistic flair and intellectual component added.

Infusion of Theatrical Elements

Looking into the market territory of theater, Cirque du Soleil also introduced new non-circus elements such as a plot line and with it the intellectual richness, artistic music and dance, and diversity of performances. By incorporating all these components, which were an innovation in the circus industry, into its program, Cirque du Soleil managed to create more sophisticated performances. Moreover, by introducing the concept of a variety of performances and thus giving people a reason to go to the circus more often, Cirque du Soleil significantly increased existing demand.

An Unprecedented Value Proposition

In summary, Cirque du Soleil offers the best of circus and theater, while minimizing or eliminating everything else. Thanks to this unprecedented value proposition, Cirque du Soleil created a blue ocean and invented a new kind of live entertainment that was markedly distinct from both the traditional circus and the traditional theater. At the same time, by abandoning many of the most expensive components of the circus, the company managed to sharply reduce its costs, thereby achieving both differentiation and low costs simultaneously. Cirque du Soleil took a strategic step by bringing its ticket prices closer to those of the theater. Ticket prices were several times higher than the level accepted in the circus industry, but they were attractive to adult viewers accustomed to theater ticket prices.

The Dwindling Impact of Circus Stars

Similarly, when the circus industry started inviting stars, the so-called circus stars seemed quite insignificant compared to movie stars in the minds of viewers. And again, this tactic required major expenses and had practically no impact on the audience. The idea of three rings also faded away. Such shows not only created tension for viewers forced to quickly shift their gaze from one ring to another, but also required more performers, leading to higher costs. Renting out premises for retail outlets and selling goods between rows seemed like a good way to make a profit, but in practice it turned out that the inflated prices kept viewers from making purchases and left them feeling cheated.

The Essence of Circus Appeal: Big Tops, Clowns, and Classic Acts

All the perennial appeal of the circus boiled down to three main factors: the big top, clowns, and classic circus acts of various kinds of acrobatics and unicycling. Therefore, Cirque du Soleil retained clowns, but their humor became more subtle and refined rather than vulgar. The big top was refined, yet it was the big top that, ironically, many circuses had abandoned in favor of renting venues. Seeing that the big top alone was the symbol that embodied the magic of the circus, Cirque du Soleil created a classic circus symbol distinguished by its magnificent exterior finish and increased comfort. Such tents evoked thoughts of the great and legendary circuses. Sawdust and hard benches were removed.

Evolution of Circus Acts: Elegance, Artistry, and Intellectual Components

The acrobatic and other breathtaking acts remained but began to play a smaller role. They were made more elegant with an artistic flair and intellectual component added. Looking into the market territory of theater, Cirque du Soleil also introduced new non-circus elements such as a plot line and with it the intellectual richness, artistic music and dance, and diversity of performances. All these elements, which were an innovation in the circus industry, were taken from the alternative live entertainment industry - the theater business. For example, if in traditional circuses the acts are just a series of performances unrelated to each other, then each Cirque du Soleil creation, on the contrary, had a theme and plot, thereby resembling a theatrical performance to some extent. Although the theme was set vaguely (this was done deliberately), it brought harmony and an element of intellect to the show without limiting the number of circus acts themselves.

Borrowing from Broadway: Variety, Music, and Dance

In addition, Cirque du Soleil borrowed some ideas from Broadway shows. For example, it presents a variety of programs and productions, not traditional “one size fits all” shows. Again, following the example of Broadway shows, each Cirque du Soleil performance has appropriate musical accompaniment that governs (rather than overrides) the visual component, lighting and duration of each performance. The program also includes beautiful dances - the idea was taken from theater and ballet. By incorporating all these components into its program, Cirque du Soleil managed to create more sophisticated performances. Moreover, by introducing the concept of a variety of productions and thus giving people a reason to go to the circus more often, Cirque du Soleil significantly increased existing demand.

Summary: Cirque du Soleil's Unprecedented Value Proposition

In summary, Cirque du Soleil offers the best circus and theater has to offer, while minimizing or eliminating everything else. Thanks to this unprecedented value proposition, Cirque du Soleil created a blue ocean and invented a new kind of live entertainment that was markedly distinct from both the traditional circus and the traditional theater. At the same time, by abandoning many of the most expensive components of the circus, the company managed to sharply reduce its costs, thereby achieving both differentiation and low costs simultaneously. Cirque du Soleil took a strategic step by bringing its ticket prices closer to those of the theater. Ticket prices were several times higher than the level accepted in the circus industry, but they were attractive to adult viewers accustomed to theater ticket prices.

Developing and Executing a Blue Ocean Strategy

Although economic conditions indicate an increasing need to create blue oceans, there is a persistent belief that the chances of success decrease when a company goes beyond the existing industry space in its activities. How to succeed in blue oceans? What should companies do to maximize opportunities while minimizing the risks associated with developing and implementing a blue ocean strategy? If you do not have a good enough understanding of the principles of expanding opportunities and minimizing risks that underlie the creation and conquest of blue oceans, your chances of failure in creating a blue ocean will be high.

Of course, there is no such thing as a risk-free strategy. Strategy always involves opportunities and risks - regardless of whether events occur in a red or blue ocean. However, at present, the balance on the playing field is disrupted in favor of tools and analytical frameworks designed to succeed in red oceans. Until this changes, red oceans will continue to prevail in a company's strategic plans, even if the imperative to create blue oceans becomes even more obvious. Perhaps this is why, despite repeated calls for companies to move beyond the existing industry space, they have not taken any serious steps in this direction.

| Development Principles | Risk Factor for Each Principle |

|---|---|

| Reconstruct Market Boundaries | Search Risk |

| Focus on the Big Picture, Not the Numbers | Planning Risk |

| Go Beyond Existing Demand | Scale Risk |

| Define the Strategic Sequence Correctly | Business Model Risk |

| Principles of Implementation | Risk Factor for Each Principle |

| Overcome Key Organizational Barriers | Organizational Risk |

| Embed Implementation in Strategy | Management Risk |

Source: Blue Ocean Strategy is a book published in 2004 written by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, professors at INSEAD, and the name of the marketing theory detailed on the book

Elon Musk's radically angular Cybertruck pickup shocked audiences in 2019 with its geometric stainless steel body evoking sci-fi movies and 80s cars. Its unconventional form draws criticism along with praise for its boldly futuristic look. Behind the origami-esque styling lies a highly capable electric truck with armored doors, adaptive air suspension, and up to 500km range. But with pickup buyers traditionally loyal to brands like Ford and RAM, does the Cybertruck's divisive design represent an innovation that will disrupt and transform the market or an alienating bust?

Elon Musk's radically angular Cybertruck pickup shocked audiences in 2019 with its geometric stainless steel body evoking sci-fi movies and 80s cars. Its unconventional form draws criticism along with praise for its boldly futuristic look. Behind the origami-esque styling lies a highly capable electric truck with armored doors, adaptive air suspension, and up to 500km range. But with pickup buyers traditionally loyal to brands like Ford and RAM, does the Cybertruck's divisive design represent an innovation that will disrupt and transform the market or an alienating bust?

Explore how neuromarketing reveals the brain's role in purchase decisions based on pleasure and suffering. Learn about the endowment effect and its intriguing parallels, as well as the diminishing marginal utility of wealth. Uncover key factors influencing buying choices and their implications for marketing.

Explore how neuromarketing reveals the brain's role in purchase decisions based on pleasure and suffering. Learn about the endowment effect and its intriguing parallels, as well as the diminishing marginal utility of wealth. Uncover key factors influencing buying choices and their implications for marketing.

YouTube's origin traces back to three individuals from the PayPal mafia: Chad Hurley, Jawed Karim, and Steve Chen. After eBay acquired PayPal, they sought a new venture. Chad, an artist turned IT enthusiast, designed PayPal's logo. Steven, a Taiwanese math graduate, owned his tech company. Jawed, born in GDR, created an autonomous messaging system.

Inspired by the 2004 tsunami's lack of online footage, Jawed proposed a video hosting idea. Initially conceived as a dating site, YouTube emerged in 2005. Despite various versions of the creation story, the trio's collaboration birthed the beloved platform.

YouTube's San Bruno, California, roots saw its initial non-commercial phase. Rapidly gaining 9 million daily users, an ad marked its commercial turn. Jawed's 18-20-second zoo video on April 23, 2005, marked the platform's video era. By 2006, significant investment and over 65,000 videos propelled YouTube to global fame, attracting over 100 million daily views.

YouTube's origin traces back to three individuals from the PayPal mafia: Chad Hurley, Jawed Karim, and Steve Chen. After eBay acquired PayPal, they sought a new venture. Chad, an artist turned IT enthusiast, designed PayPal's logo. Steven, a Taiwanese math graduate, owned his tech company. Jawed, born in GDR, created an autonomous messaging system.

Inspired by the 2004 tsunami's lack of online footage, Jawed proposed a video hosting idea. Initially conceived as a dating site, YouTube emerged in 2005. Despite various versions of the creation story, the trio's collaboration birthed the beloved platform.

YouTube's San Bruno, California, roots saw its initial non-commercial phase. Rapidly gaining 9 million daily users, an ad marked its commercial turn. Jawed's 18-20-second zoo video on April 23, 2005, marked the platform's video era. By 2006, significant investment and over 65,000 videos propelled YouTube to global fame, attracting over 100 million daily views.